This is a long post by any standard. The reason this is so is because I discuss a brief history of the Korean Peninsula, the motivations and the fears that each player holds closest to its heart and briefly consider major flare-ups in the past and their impact on stability in the peninsula. Once we have these laid out, the stage is all set to reason about whether the current chain of events could send the peninsula into the abyss of instability. I talk about the base case scenario - a starting point from where one could reason about plausible alternatives that could look a lot worse. Happy reading!

RISING TENSIONS (2009-2H2010)

The Korean peninsula is in the news and the chain of events does not look good. Back in April 5, 2009, North Korea (NK) test launched Taepodong-2, a multi-stage ballistic missile with a range of 4,000km. A week later the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) unanimously authorized additional sanctions on North Korea

[1] Six Party Talks refers to the series of joint-diplomatic engagements involving China , Japan , North Korea , South Korea , Russia and the US North Korea ’s nuclear weapons capabilities, for bringing North Korea

In May 2010, a fresh round of tensions were trigged by investigations that concluded [1] that a North Korean torpedo was responsible for the sinking of the ROKS Cheonan, a South Korean anti-submarine patrol corvette, and the consequent death of 46 onboard sailors. North Korea

[1] North Korea China and Russia

[2] The sea between Japan and the peninsula is referred to as ‘East Sea ’ by South Korea , ‘East Korean Sea ’ by North Korea and ‘Sea of Japan’ by Japan

WITHER PEACE?

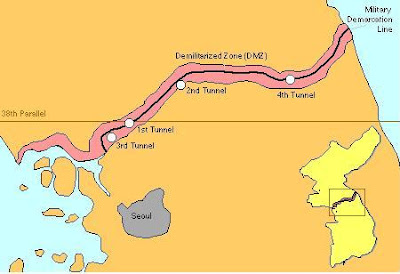

What do these events mean for peace in the Korean peninsula? In the strict sense of the word ‘peace’ the question is meaningless as the two Koreas continue to be officially at war since 1950 as the July 1953 armistice was never followed through with a peace treaty. Therefore in the current context, we define peace as a state wherein there is no material violation of the land, sea or air space of either country. In our view the chance that peace is shattered is slim; it is no higher than it has been prior to earlier periods of escalating coercive posturing and fatal skirmishes. To see this, we discuss the strategic interests of the main players in the region, their reactions to past outbreaks of hostilities in the peninsula and review the impact of current events on the interlocking geopolitical interests in the region.

THE KOREAN PENINSULA OVER THE PAST 150 YEARS

With the Treaty of Ganghwa signed in February 1876, the Korean peninsula passed from being a Qing Dynasty [1] protectorate to a Japanese protectorate. Japan Japan North Korea invaded South Korea Koreas South Korea Koreas

[1] Its successor state is the modern day China

BACKGROUND AND STRATEGIC INTERESTS OF KEY PLAYERS

North Korea

The North Korean regime is a totalitarian dictatorship that has outlasted its foundational supporter, the Soviet Union . It has been on a deathwatch since 1991 [1] and more so since the death of Kim Il-Sung in July 1994, its former President and father of the current President, Kim Il-Jong (KJI). Those who predicted its imminent demise have had a lot of explaining to do. Perhaps they were right though if one were to think of demise as a process as opposed to an event.

North Korea Iran , Libya , Pakistan , Syria and Yemen and enjoys the diplomatic support of Cuba and Venezuela China replaced the Soviet Union as its principal backer. While China

In recent history no totalitarian regime has survived for long - some have adapted (China , late 1970s), some disintegrated following failed reforms (Soviet Union, 1988-1991), some were overthrown (Romania , 1980s) and some remained in suspended animation prior to collapse (Albania North Korea

The normalization of trade links will prevent an economic implosion and grant the regime an implicit legitimacy. South Korea , Japan North Korea has a paranoid fear that the US US US North Korea

The regime’s seemingly irrational behavior and frequent reneging on its international commitments can be explained by the hypothesis that it intends to highlight its nuisance potential as a bargaining chip in order to achieve its two principal goals. The North Korean regime thinks it can do this without attracting military retribution as it knows it cannot push it too hard (as long as it is backed by China or another major power) as else that would plunge the Korean Peninsula into geopolitical instability [5]. At the same time, this puts a bound on the perceived irrationality of the North Korean regime.

[1] The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

[2] These mainly relate to trade in missile and nuclear weapons technologies.

[3] These are no different from what China

[4] US’ mutual defense treaties with Japan and South Korea North Korea has repeatedly threatened war against Japan and South Korea

[5] Beyond its weapons of mass destruction, North Korea

China

The Chinese language has an idiom - “if the lips are gone, the teeth will be cold”. It is used to mean that when a protective element fails, the one that is protected, despite its apparent strength, runs a high risk of failing. This is how the Qing Dynasty and its successor, the present day China

China however remains concerned that the North Korean regime’s rhetoric and irrational military acts might precipitate a crisis leading to a full blown invasion of North Korea by the US China would exercise the leverage of its considerable economic, diplomatic and defense linkages with North Korea

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 produced an outward-looking, modern industrial state of Japan [1]. In 1876, Japan Japan gained a foothold in the peninsula which allowed it to launch two major attacks on the Qing Dynasty in the subsequent decades - the first resulted in the loss of the Liaodong Peninsula and Taiwan in 1885 to Japan and the second took place in 1937 resulting in the loss of the resource rich Manchuria .

Following its defeat in World War II , Japan China however continues to view the Korean Peninsula through the prism of the teeth and lips metaphor, with the US replacing Japan China ’s principal goal in the Korean Peninsula is the maintenance of the status quo whereby the peninsula remains partitioned between the two Koreas China and the 30,000 US troops stationed in South Korea China to focus on Taiwan Japan China of a significant portion of the FDI from South Korea

[1] China’s security perceptions over the Peninsula are rooted in Japan’s actions during the late 19th century through the end of WWI. We therefore briefly discuss Japan in this section.

[2] Article 9 of the Japanese constitution specifically prohibits Japan

[3] China expects that a reunified Korea China , the reunification will trigger a rapid nuclearization of Japan China ’s perspective, two Koreas

South Korea

Over the years however, South Korean elites have developed a view that the North Korean regime is essentially a force for bad; the reasons for which are many:

· 1950-53: The North Korean invasion of South Korea

· 1950-till date: North Korea

· 1953-early 2000s: North Korea

· 1971 and 1974: North Korean agents made an assassination attempt on the then South Korean President, Park Chung Hee. While the President survived both attempts, the second attempt killed his wife.

· 1987: North Korean agents planted explosives in a Korean Airlines flight that killed all 115 people on board. The attack is purported to have been triggered by South Korea ’s decision to exclude North Korea

· 1990s-till date: North Korean has repeatedly threatened South Korea

South Korea has five principal goals in the peninsula - nudge the North Korean government towards democratization, bring about a considerable improvement of human rights situation in the North, prevent an economic implosion in the North Korea, prevent the reignition of open hostilities and, over a longer term, achieve a reunification between the two Koreas.

The first goal bears ideological importance and rhymes with the view of the other major powers. Besides, South Korea believes that without incremental democratization, North Korea North Korea North Korea does not initiate a war, destabilization would cause millions of refugees to pour into South Korea North Korea

[1] North Korea

Japan

Russia

The Soviet Union’s interest in the Korean Peninsula North Korea

In the modern context however, Russia ’s contribution is no longer the major component in North Korea North Korea ’s trade relations with Russia Russia ’s focus since its recovery in early 2000s from the debilitating effects of the Soviet breakup has been the Balkans, the Caucasus region and Central Asia . Each of these regions is far away from the Korean Peninsula and, the peninsula itself is separated from Russia Russia Russia North Korea would require a positive vote from Russia

While Russia generally agrees with the international community that respect for human rights and greater societal openness is important in North Korea

The diplomatic surplus that Russia generates out of the choices it makes with regards to North Korea will be put to work elsewhere - on the tradeoffs it needs to make in the Caucasus region, in Eastern Europe and issues with the United States

USA

The US can easily address the problem in the Korean Peninsula - it could sign a bilateral nonaggression pact with North Korea and pave way for normalization of the North Korea’s trade relations in return for the latter’s abjuration of the use of force against South Korea and Japan, its cooperation for the implementation of mechanisms to allow a verifiable, non-reversible and an externally enforceable rollback of its (NK’s) own nuclear weapons capabilities and its bringing about a visible improvement in the human rights situation (in NK). One might wonder then why this has not been done yet. There are several reasons for this.

US has five objectives in the interim - prevent an implosion of the North Korean regime until an amenable faction emerges, prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons and ballistic missile technologies by North Korea, remain committed to not making any material concessions until irreversible mechanisms for a complete rollback of North Korea’s nuclear weapons capabilities have been put in place, encourage China to use its considerable leverage with the regime to prevent the latter from forcing a showdown in the peninsula and tighten the screws on money laundering channels and financial institutions that the North Korean regime uses to settle its foreign transactions [1].

First, North Korea has a paranoid distrust of the US North Korea North Korea

[1] The North Korean regime is heavily dependent on such transactions. Besides, access to such transactions reduces the effectiveness of aid and trade and levers that China , Japan and South Korea have with North Korea

THE QUESTION OF PEACE

We have noted right in the beginning that the chain of events over the past five quarters has been rather grim. However, when one considers the recent events in the light of past patches of flare-ups in the Korean Peninsula Koreas

Flare-ups Since the 1953 Armistice

Flare-ups Since the 1953 Armistice

· 1968: North Korean patrol boats seize a U.S.

· Jan 19, 1968: North Korean army unit enters Seoul

· Apr 15, 1969: A US Navy reconnaissance plane was shot down over the East Sea

· 1974: North Korean agents kill South Korea ’s first lady in their second attempt to assassinate President Park

· 1993: Just two years after the dissolution of its major backer, the Soviet Union, North Korea

· 1996: A North Korea submarine runs aground the South Korea

· 1999: Sea skirmish between North and South Korea

· 2001: President Bush halts all diplomatic talks with North Korea

· 2002: Yellow Sea skirmish leads to the death of six South Korean and a dozen North Koreans. US President George Bush designates North Korea as being part of an “Axis of Evil” in his State of the Union address and suspends US North Korea

· Oct 9, 2006: North Korea

· 2008: The newly elected South Korean President, Lee Myung-Bak, reverses the decade-old Sunshine Policy and links further improvement in ties between the two Koreas

· May 25, 2009: North Korea

[1] Ironically, President Park

In Recent Times

In the present times we are watching an increasingly hardened stance on the North by South Korea which is however being balanced by an increasingly accommodative, and at times, supportive China Russia Japan

With the knowledge that it cannot be pushed too hard, North Korea

[1] Dick K. Nanto and Emma Chanlett-Avery, “North Korea

Will the Peninsula Heat Up Further?

A nuclear armed North Korea is unacceptable to the US South Africa and Brazil

Thus the latest round is likely to be as exciting as watching paint dry. A key assumption is that the key parties follow an information-complete rational behavior. What could happen should this assumption fail to hold? How far can North Korea

[1] On May 1, 2003, in a speech delivered on board the USS Abraham Lincoln, US President G.W. Bush declared an end to major combat operations relating to the second US-led invasion of Iraq. Iraq continues to fester, still.

No comments:

Post a Comment